Flail Chest Management

Question# 762

There is conflicting data on whether to splint and do PPV. What is the RPPEO’s stance?

Answer:

As you’re aware, the ribs cover the thoracic cavity, protecting the lungs and other mediastinal structures. Damage to the chest wall, usually occurring as the result of blunt trauma, is important to assess and treat as there can be severe and life-threatening injuries to the underlying structures, not to mention significant morbidity. Rib fractures are a marker of more severe injuries and occurs in 5-13% of patients with chest wall injuries, and 90% of patients with rib fractures will also have other traumatic injuries (as an example, in one study, head injury was present in 25 percent of patients diagnosed with flail chest). It’s important to remember, that particularly in elderly patients, minor trauma can cause serious injuries; so keep a high index of suspicion in this patient cohort.

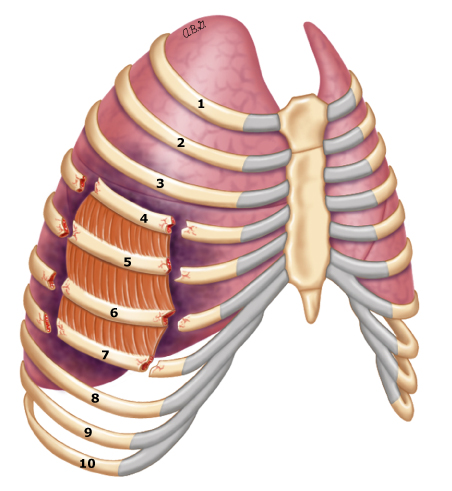

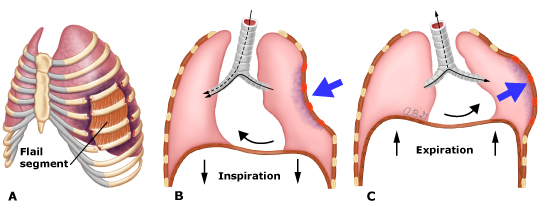

With respect to flail chest, we define this as unstable section of chest wall that occurs when three or more adjacent ribs are each fractured in two or more places. This creates a floating segment of several rib sections and soft tissues between them. Here is a video online of a very significant flail chest (https://twitter.com/EM_RESUS/status/1744092475554185384). These injuries are often due to high-energy trauma, and are associated with a high risk of significant associated injuries (e.g. pulmonary contusions, pnemuothoraces, hemothorax, sternal fractures, intra-abdominal injuries, upper extremity injuries, etc.).

©2024 UpToDate, Inc

©2024 UpToDate, Inc

This section of chest wall exhibits paradoxical motion [moving in the opposite direction of the un-injured, normal functioning chest wall (chest wall being pulled in with inspiration and pushed out with expiration)]. While this is a tell-tale sign, it is often difficult to see, especially in the context of obese patients, muscular patients, patients with large amounts of breast tissue, or if the flail segment is small. It’s thus tremendously important to palpate for injuries. Patients may also report a feeling of clicking or movement with deep inspiration or coughing.

©2024 UpToDate, Inc

©2024 UpToDate, Inc

In terms of management and treatment, the cornerstone prehospital treatment is a detailed and thorough trauma survey and management of the A-B-Cs. This means c-collar application and rapid transport to a trauma centre (as per the FTTG). Consider the application of supplemental oxygen in these patients as well. Further, the trauma patient should be completely undressed so the entire chest and back can be examined. Look for signs of trauma such as ecchymosis, hematomas, or imprints from seatbelts. Feel for tenderness, pain on palpation, crepitus, deformity, or depression, and auscultate early and often. As with all trauma patients, hypothermia significantly impacts morbidity and mortality: so keep them covered, dry, and warm. With respect to ‘C’, it’s important to keep patients euvolemic and avoid HYPERvolemia due to risk of pulmonary edema in contused pulmonary tissue.

If the patient isn’t showing signs of airway or breathing compromise, a conservative approach is prudent. Applying end-tidal capnography will also afford to an opportunity to further assess these patients. If there are signs of respiratory distress (tachypnea, laboured or shallow breathing, accessory muscle use, hypoxia, hypercapnia etc.) or hemodynamic instability, these need to be addressed (i.e. airway management, chest-needles, etc.).

There is no evidence that splinting, or stabilization has positive impacts, and in fact, it may actually impair ventilation by restricting chest wall expansion and interfering with proper respiratory mechanics. Thus, this is no longer recommended.

With respect to PPV, we need to be very cautious in this patient population, as PPV in an undifferentiated patient with flail chest is often associated with pneumothorax, which can convert to tension with excessive PPV. Provide PPV if indicated but be aware of the risk of tension pneumothorax.

What does help in this patient is analgesia. Pain, and underlying lung injury are the cause of respiratory compromise secondary to blunt chest trauma. Due to the pain, patients will be splinting. This splinting leads to tidal volume reduction and hypoventilation leading to poor oxygenation and hypercapnia.

Adequate and aggressive analgesia is thus critical for the early management of these patients. It’s important to strike a balance however, as opiates can blunt an already fragile respiratory system. Analgesia also allows patients to deep breath and cough, clearing secretions and decreasing their risk of pneumonias.

References

Field Trauma Triage Guidelines

BLS PCS - Chest Trauma Standard

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-evaluation-and-management-of-blunt-thoracic-trauma-in-adults?sectionName=PREHOSPITAL%20MANAGEMENT&search=flail%20chest&topicRef=13861&anchor=H4&source=see_link#H4

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-evaluation-and-management-of-chest-wall-trauma-in-adults?search=flail%20chest&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~36&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H15009018

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/inpatient-management-of-traumatic-rib-fractures-and-flail-chest-in-adults?search=flail%20chest&topicRef=13861&source=see_link

- https://www.ems1.com/trauma/articles/back-to-the-basics-chest-trauma-F6AtcGH8Z09Kgt36/

Published

ALSPCS Version

Views

Please reference the MOST RECENT ALS PCS for updates and changes to these directives.